INTRODUCTION

Being the first social institution individuals enter, the family has an instrumental role in developing a sense of morality and justice in its members. Conceptualising justice and the right principles to govern society’s political institutions has been of central interest to political philosophy, yet the idea of applying the very same principles to family’s internal structure has frequently been dismissed based on a view of the family as non-political by nature. In this paper, I will object to this view and argue that the family not only influences but is itself a political institution and show that to fulfil its role of the first moral school, relations within the family should be subjected to the application of the principles of justice.

To do this, I will first specify how this paper understands these principles by introducing the justice theory developed by Rawls and define the concepts of the family and the relations within it. Employing Okin’s and feminist critiques, I will then argue that the family is not naturally just and that it cannot be excluded from the scope of the principles if it is to serve the purpose of a morally formative institution. Building on this claim, I will demonstrate why it is right that the same political principles of justice that apply to other institutions should govern relations within the family, and finally, I will discuss contemporary structural changes in the family and argue they amplify the need for the principles of justice to apply to relations within it.

When examining the theories considered in this paper, I will be taking a feminist approach and assume the authors meant to include women in their application. An additional distinction to be made is that between justice in the family and justice of the family. While the former regards applying the principles of justice directly to familial relations, the latter addresses the question of whether it is just for the family as such to exist (Munoz-Darde, 1998). Arguments made in this paper only relate to justice in the family and do not aim to justify its existence. Similarly, I will only attempt to show why the principles of justice should apply to familial relations, not how this should be done, as the discussion of policies is beyond the scope of this paper.

DEFINING THE PRINCIPLES OF JUSTICE AND THE FAMILY

The idea of justice and its principles is a broad one, concerning different subjects depending on the context. The most comprehensive justice theory that addresses the family is that of Rawls which is why, for the purpose of this paper, I will derive the principles directly from his work. To formulate them, Rawls begins with defining a well-ordered society as a fair system of cooperation among free and equal citizens who agree to be governed by just principles (Rawls, 2003). For Rawls, the primary subject of justice is what he refers to as the basic structure or the main social institutions and ‘the way they assign basic rights and duties and regulate the division of advantages’ (Rawls, 2003; pp. 10). To illustrate, the basic structure comprises institutions like the political constitution, legal system, economy or family. By the nature of these, participation in the basic structure is non-voluntary and non-excludable, meaning it affects the lives of all citizens and its rules can be enforced. Precisely for this reason, principles of justice apply to the basic structure and the basic structure only. To ensure fairness and impartiality, Rawls creates a ‘veil of ignorance’ that prevents people from knowing what their talents, conception of good, and social position like race, class, sexuality (Rawls, 1971) and gender (Rawls, 2003) are and leads them to the purest conception of justice. In what Rawls calls the ‘original position’, he arrives at its two principles. The first entails fair distribution of ‘equal basic liberties’ such as freedom of thought and liberty of conscience, political freedoms and personal integrity, while the second regards economic liberties, namely the ‘fair equality of opportunity’ ensuring those with similar talents have the same prospect of success, and the difference principle that allows inequalities in wealth and income only if they ‘are to be to the greatest benefit of the least-advantaged members of society’ (Rawls, 2003; pp. 42-43).

In regard to the family, a ‘group of people united by ties of partnership and parenthood and consisting of a pair of adults and their socially recognised children’ (Encyklopædia Britannica, 2019) in its nuclear form will be assumed. I will further be assuming the monogamous hetero-biological family in most sections for two reasons; to stay consistent with Rawlsian account of family and to show that even such idealised family should be subjected to the principles of justice. Other family structures will be discussed in the last section.

I

Considering Rawls’ inclusion of the family in the basic structure as established in the previous section, it seems clear and evident that the principles of justice should apply to relations within it, ‘ensuring [children’s] moral development’ (Rawls, 2003, pp. 163). However, when addressing the family in regard to justice later in his work, Rawls surprisingly purports we would not ‘want political principles of justice to apply directly to the internal life of the family’ (Rawls, 2003; pp. 165) for families should be governed by virtues nobler than justice, like love or family unit (Kearns, 1983). In other words, Rawls and others who argue in a similar way see family’s internal structure as either inherently just or above justice. Recalling the definition of the principles, the former would mean the relations are such as to ensure all members have equal basic and political liberties, fair equality of opportunity and that any inequalities arising in the family are to the greatest benefit of the least-advantaged ones, while the latter suggests no need for these at all.

To object to what seems contradictory in Rawls’ view, I shall argue in two layers: that family is not as inherently just and noble as Rawls suggests, and that it cannot stand above justice if it is to develop such sense of justice in children as we expect in adult members of society. One of the first to point out the family is not a just institution were Okin and Kearns. Okin strongly disagrees with the idealised family and argues that ‘marriage and family, as currently practised in our society, are unjust institutions’ (Okin, 1991; pp. 135). If most of the unpaid labour in the household including nurturing and caring for children is done by women in the style of the traditional gender-driven division of labour within the family, she further argues, not only does it lead to the ‘related economic dependency and restricted options for women’ (Okin, 1991; pp. 9), thereby violating the second principle of fair equality of opportunity in regard to the choice of occupation of both sexes, but it also undermines family’s role of the first school of moral development as children learn from their parents. Arguing from a similar position, Kearns claims that by excluding family from the scope of the principles, ‘female and male children will have different experiences’ and the ‘institutional injustice is likely to prevent both sexes from developing the crucial sense of justice’ (Kearns, 1983; pp. 36). What both feminist critiques point toward is that a social environment that is not founded on the principles of justice will fail to develop that sense of justice children will need as citizens of a just society (Okin, 1991). If we want the family to fulfil its universally recognised role of the first moral school, principles of justice need to apply to the parental relation within it.

II

A possible objection to the argument this paper has made so far is that since family is a personal rather than political institution, personal relations should not be subjected to political justice. There are two lines of response to the view of a dichotomy between the political and personal spheres (Okin, 1991). One addresses how political and legal systems determine the way families function, and how what happens in the family affects the political domain in return, while the second one focuses on how familial relations bear the same key features as political institutions and it is therefore right to subject them to political justice.

Among other institutions of the political sphere, the legislation determines all sorts of familial matters like conditions of marriage and who is the legal child of whom. Directly through these laws, the political domain affects how families function by being ‘responsible for the background rules that affect people’s domestic behaviours’ (Okin, 1991; pp. 130). In return, what goes on in families determines the nature of the political domain. Recalling the argument from moral school, the failure to subject familial relations to the political principles of justice and, consequently, to abolish the gender-structured division of labour within the family, boys and girls learn a different sense of justice and self-conception. Usually, this leads boys to develop ‘a greater need and capacity for individuation and orientation toward achieving public status’ and cause ‘mothering itself to reproduce in girls’ (Okin, 1991; pp. 132). Now consider the disproportionate number of men in positions of political power as a possible implication. Taking the recent abortion ban in Alabama as an illustrative example, we see it is very well possible to have an all-male council decide on an issue that is just as much a matter of family justice as it is of women’s rights (Ritu Prasad, 2019). Maybe the political institutions can be just only once the gender-structured domestic life is subjected to the just principles. And maybe then, female representatives will be present in deciding on matters regarding women’s reproductive rights.

Another way of proving the family belongs to the political domain is by showing how the parent-child relation seems to bear political features itself. Clayton elaborately argues that the political institutions of the basic structure (which he sees as the primary subject of political justice) have three key features: they are non-voluntary, have significant effect on individuals’ lives and self-conception and are coercive in the sense that their rules are enforceable. Apart from including the political institutions within the scope of political justice, he goes on to argue that parents and children too are in ‘a non-voluntary coercive relationship that has profound effects on the child’s life prospects and her self-conception’ (Clayton, 2006; pp. 93-94). Since it can be argued that the parent-child relationship is parallel to that of the state and its citizens, he continues, it follows that parental conduct should be governed by the same principles as the political conduct. In other words, the familial relation between parents and children should be subjected to the principles of justice to prevent parents from exercising their authority in contradiction to the public reason (Clayton, 2006). I imagine a possible objection might arise around the lines that parents will not naturally harm their own children. While this might hold for the idealised Rawlsian family, considering the structural changes to the contemporary one, the argument is more difficult to defend.

III

Arguing the family stands above justice fails to pay attention to ‘what happens in such groupings when they fail to meet this saintly ideal’ (Okin, 1991; pp. 29). With the number of divorces increasing, and same-sex marriages becoming legal, failing to meet the traditionalist ideal becomes more common (Anderson, 2014). To illustrate how this intensifies the need for principles of justice within families, I considered patchwork families where at least one of the adults bears a child from their previous marriage. I argue that the ostensible love and affection are not natural in relations between step-parents and step-children which can at times result in evident injustice, like treating one’s own child differently than the step-child. Such experiences diminish children’s chance of developing the sense of justice the society requires. This brief but illustrative example is one among a variety that refute the view that relations within the family should be governed by nobler principles than those of justice. In some cases, love and affection are not possible in a family (Okin, 1991).

CONCLUSION

Using a set definition of Rawlsian principles of justice and considering the matter from a feminist standpoint, I have argued that these should govern relations within the family. I have done this by showing that the institution of family is not inherently just and if it is to fulfil its universally recognised role of the first moral school, justice needs to be applied to the relation between parents for children to have a chance of acquiring a sense of justice. I have further argued that its principles need to be political by showing two ways in which the family belongs to the political domain and therefore should not be excluded from the scope of political justice. Finally, I have considered contemporary structural changes to the family and argued that once the ideal traditionalist family is no longer assumed, applying the principles to the family becomes even more important. Every argument I presented in this paper supports the conclusion that a just society governed by political principles of justice can only be possible if we apply the very same principles to the internal structure of the institution that first teaches us what justice means–to the family.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, J. (2014) The Impact of Family Structure on the Health of Children: Effects of Divorce. The Linacre Quarterly. [Online] 81 (4), 378–387. [online]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4240051/.

Clayton, M. (2006) Justice and legitimacy in upbringing. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. pp 94-93.

Kearns, D. (1983). A Theory of Justice—and Love; Rawls on the Family. Politics, 18 (2), pp. 36-42.

Munoz-Darde, V. (1998). Rawls, Justice in the Family and Justice of the Family. The Philosophical Quarterly, 48(192), pp. 335-352.

Okin, S. M. (1989). Justice, Gender And The Family. New York: Basic Books, Inc.

Prine Pauls, E. (2019) Nuclear family | anthropology. Encyclopædia Britannica [online]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/nuclear-family.

Rawls, J. and Kelly, E. (2003). Justice as fairness. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Reshef, Y. (2012). Justice, children and family. LSE Theses Online. Available at: http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/549/.

Ritu Prasad (2019) Alabama abortion ban: Should men have a say in the debate? BBC News. 17 May. [online]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-48262238.

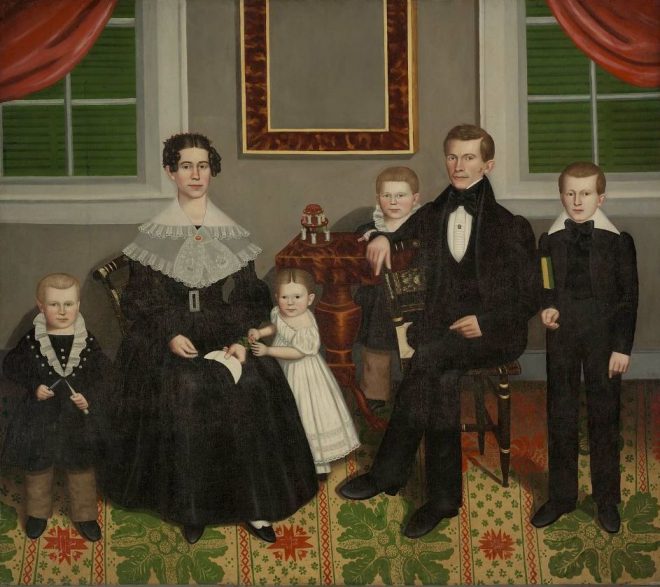

Featured image: Erastus Salisbury Field, ca. 1839 | Joseph Moore and His Family

Leave a Reply